Asian Luxury

The fashion cult reaches unexpected heights in Tokyo, where the flagship stores built for the top brands are both spectacular boutiques and corporate logos.

We can’t pretend to understand Japan. Anyone visiting this empire of signs empathizes with the perplexity of Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson in Sofia Coppola’s film. Like them, we know that the essential is lost in translation, and that we are left strayed in the labyrinths of language and custom. It is not easy to reconcile the exquisite refinement of Japanese calligraphy and gardens with the current fever for western mercantilism, nor is there a way of mapping out the road that leads from haiku to manga without accepting the traumas of Japan’s opening up to the world, from Commodore Perry to General MacArthur. Ian Buruma, who knows the country well, believes it excessive to blame its intellectual and artistic dislocations exclusively on the violence of foreign impositions. But surely its exacerbated consumerism is as much a sign of economic modernity as it is an indication of cultural malaise. Japan’s passion for fashion cannot simply be interpreted in the individualist terms of the ‘emotional luxury’ that Gilles Lipovetsky has theorized as an extreme expression of democratic hedonism and mass narcissism.

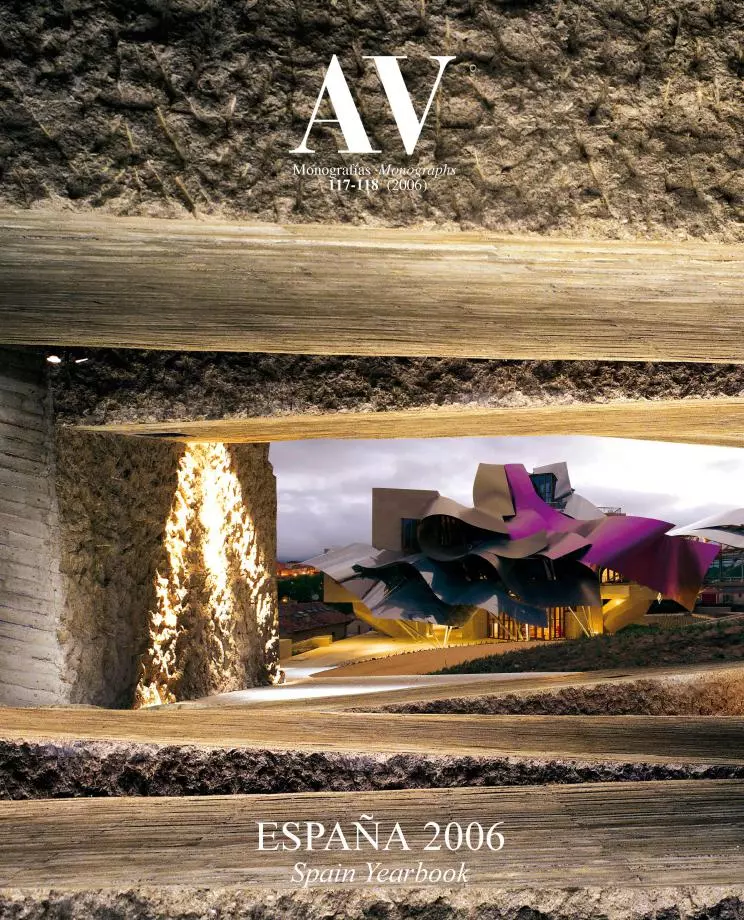

Piano’s glass brick facade for Hermès is a gulf of silence in the flashy night of Tokyo’s Ginza quarter

The district of Tokyo that was the scene of the closest thing to eternal luxury was Ginza, and after a period of decline triggered by the bursting of the stock market bubble in 1992, it still is. The area’s new seats of high-fashion houses testify to this. These include Renzo Piano’s elegant building for Hermès, with its neat facade of glass bricks and its interior characterized by a crystallographic and metallic luminosity, and Jun Aoki’s exceptional boutique for Louis Vuitton on Namiki Street, with its prefabricated GRC pieces incrusted with the same white marble used in the Taj Mahal. But the new hub of fashion trademarks is Omotesando Street, where Tadao Ando once constructed the Collezione Building with his laconic concrete surfaces, where Kengo Kuma has raised a structure for LVMH offices and outlets with a monumental latticework of vertical larchwood slats, and where the Swiss partnership of Herzog & de Meuron has carried out for the Italian firm Prada what is without a doubt the most dazzling of all, a faceted crystal with lozenges of bubbly glass that is set on the site with the blasé precision of an excessive jewel.

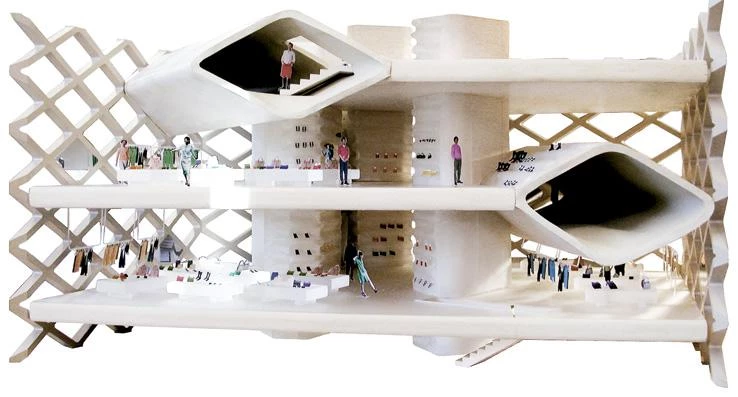

The striking flagship store for Prada in Tokyo’s Aoyama district was conceived by Herzog & de Meuron as a faceted crystal with structural lozenges that reveal on Omotesando street the uniqueness of its section.

This luxury fashion street has now brought in new neighbors, and the curiosity their fascinating facades arouse is at a par with the disappointment that their routinary interiors produce. As a matter of fact, the architects called in to create these commercial icons are almost never commissioned to design the interior spaces, which tend to be entrusted to the decoration department of the firms themselves. This separation of responsibilities partly explains the divergence of the results, but does not ease one’s irritation at the gap that stretches between the high aesthetic and symbolic ambition of the projects and the meek acceptance of a conventionally ostentatious interior imagery. Both in Toyo Ito’s work for Tod’s and in Sejima & Nishizawa’s for Dior or in Jun Aoki’s for Louis Vuitton, the promesse de bonheur announced by its urban staging is frustrated as soon as one enters. If the reader wishes to maintain ‘the suspension of disbelief’ of literary or architectural fiction, it is better to avoid visits and to concentrate on the exterior images.

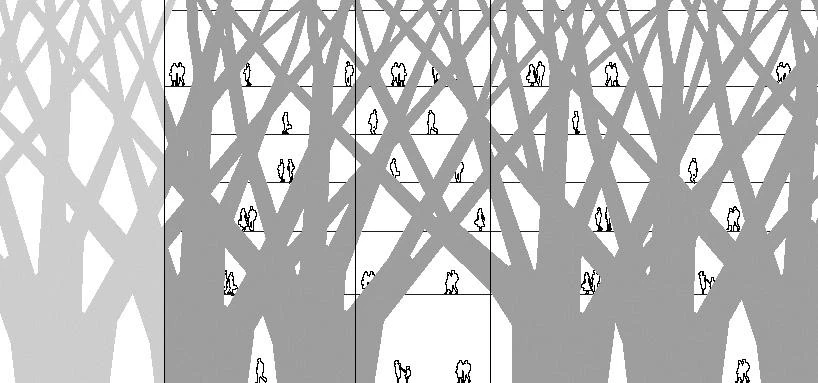

The building for the firm Tod’s on Omotesando street has been designed by Toyo Ito with an iconic concrete facade that is theatrically emphasized with the nighttime illumination to evoke a cut out, abstract forest.

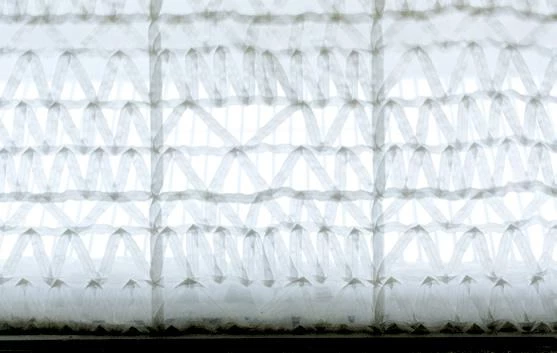

Tod’s, with its delicate facade of concrete cut out like a cardboard to evoke tree branches, is an extraordinarily efficient nighttime icon, and a daytime object that manages to draw attention to itself, buried as it is amid a gray clutter of constructions and an awkward footbridge over the street’s mad traffic. Once you step inside, however, the vulgarity of the spaces and the mediocrity of details, from the suspended ceilings to the handrails of the stairs, render the work unworthy of the author of the Sendai mediatheque. Dior, with its subtle translucent walls of curved acrylic panels and the intelligent use of urban codes to distort perception of scale with a succession of real and fictional slabs, is intriguing and seductive from the sidewalk, but perplexing when it becomes clear that the minimalist abstractions of the classical moldings and the academic paneling of upmarket traditionalism has little to do with the language of the couple that designed the Kanazawa museum. And Louis Vuitton, with its ironic piling of suitcases and trunks clad with glass and metal mesh, manages to pass on to the interior part of the richness of space suggested by the enigmatic layered facade, but here, too, the efficient organization of the complex is not as attractive as the sensual exploration of the surfaces.

Also on the same Tokyo street, the flagship stores built for Dior by Sejima & Nishizawa, and for Louis Vuitton by Jun Aoki, have in common the contrast between the refined facade skins and the routinary interiors.

In the three examples, the facade is better than the interior, the enclosures win over the spaces and the skin beats the organs. All in keeping, for sure, with an architecture at the service of cosmetics. Only the strictest fundamentalists of functional modernity will censure the prevalence of appearance over experience. For which reason it seems sensible to repeat the advice of limiting architectural consumption to that of its virtual images. This reporter, lost in translation, has suffered an overdose of reality, but promises to mend his ways.