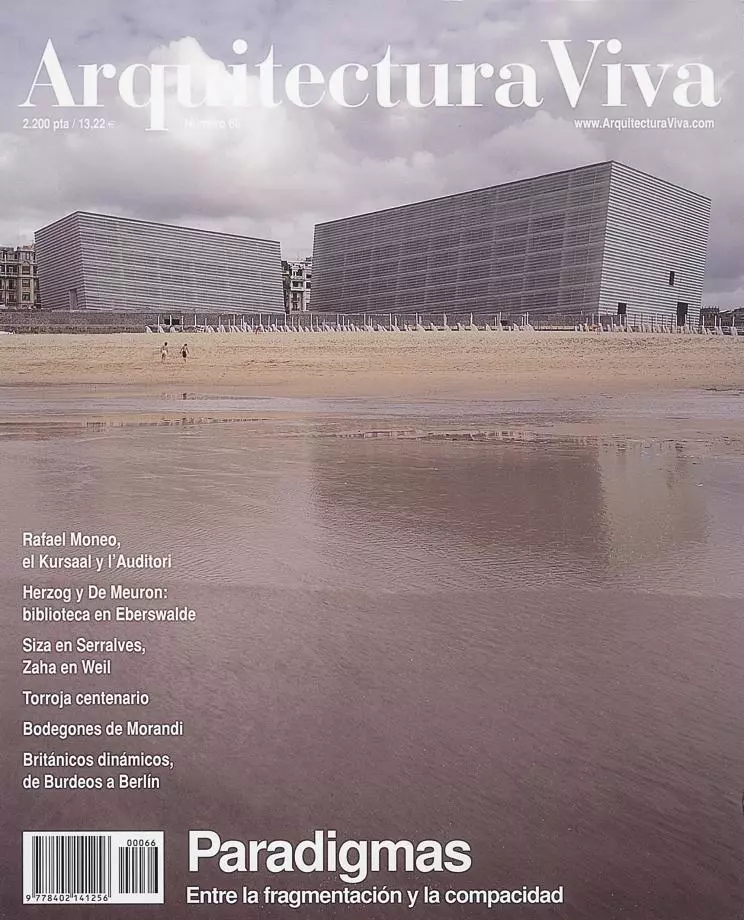

God plays no dice, but Rafael Moneo does. By throwing these colossal crystalline cubes on a card table of sand, the Spanish architect entrusts his project to a game of chance, true to the name of the building. Kursaal is a German word for casino, and a cosmopolitan term that became popular in the Belle Époque. On the sands of the Urumea River’s mouth rose, in 1922, a grand maritime Kursaal that would be the second casino of a resort city in the north of Spain. Demolished in 1973, it is on this same site that San Sebastián’s new auditorium and convention center now stands. Inheriting the old building’s name, the new Kursaal rocks between the wise play of the volumes and the aleatory docility of encounters by leaving two dice of opalescent glass abandoned on the beach of Gros, partly buried in the damp sand like ice cubes of a drink spilt with the deliberate violence that is used to turn over the shaker on the soft felt of a gambling table.

A heavy bet it was, and the controversy sparked by the project when it won the competition held in 1989 says much about its abrasive nature in a city that had chosen for itself a withered romantic identity. Yet a retrospective examination of the other entries only works to confirm how on-target the jury was in opting for Moneo. Leaving aside the picturesque light tower of Peña Ganchegui & Corrales, the tritely predictable cylinder of Mario Botta or the undulating roof evoking waves of Arata Isozaki, not even Norman Foster’s prism with technological parasols or Juan Navarro Baldeweg’s lyrical and laconic extension of the urban grid quite matched the daring brilliance of the irregular and slanted cubes that now lord over what used to be called lot K. This, to be sure, after surviving vicissitudes as complicated as those suffered by Kafka’s protagonists of the same name.

The two leaning, translucent cubes, tossed out onto the beach like dice on a card table, and gleaming like beacons in the night, recall both the mineral geometry of nature and the built artifice of the city.

Indeed, the building has on more than one occasion been on the verge of derailing. The results of the competition were announced in April 1990, but it took five years for the foundations to be laid, and the four long years of construction work since then have been full of interruptions and crises, culminating with the unfortunate collapse of part of the floor slabs and staircase on April 20, 1998. Yet the most serious setbacks for the materialization of the project arose in the course of that interminable period between the announcement of the jury’s decision and the start of building work, during which the Kursaal became the touchstone of a political debate about architectural modernity.

At first sight, the building looks rather radical. Both because of the bold geometry of the edges and the disturbing hermetism of the slanted planes, its shapes seem aggressive; but they dissolve as soon as the visitor crosses the threshold and gets submerged in the warm, watery brightness of the cedar-wood and frosted light interiors. The two timberclad concrete auditorium boxes are set back from the thick facade of translucent glass, forming narrow but luminous gorges that one ventures through with pleasure, and which lead to an orderly maze of meeting rooms and service facilities, all grouped together in a half-buried podium that denies visual protagonism to the ancillary zones.

Partly hidden like a carved iceberg, the Kursaal also mollifies its encounter with the city on Zurriola Avenue, where the entrances come under an emphatically horizontal porch flanked on one side by a restaurant run by a famous local cook and on the other by an exhibition gallery, besides several shops that serve to give this urban front an almost domestic air. And in contrast to Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, whose tempest of titanium is visible from each of the thoroughfares that lead to it, the Kursaal separates the prisms in such a way that the only street blocked by the complex still has a view to the sea, and, in demure deference to the landscape, both volumes lean meekly in opposite directions toward the most immediate geographical accidents, the mounts Urgull and Ulía.

Having conceived this project at Harvard, Rafael Moneo proposes compact forms as an alternative to the fragmented expressionism of deconstruction and the material rigor of minimalism.

Drawn up at Harvard during his tenure there as chairman of architecture of the Graduate School of Design, the Kursaal project is atypical in Moneo’s career, with no clear antecedents nor any significant influence on his subsequent work. Though it does feature some vocabulary of previous projects, not to mention elements derived from his Corbusian affiliation, from the cannons of light to the boîte à miracles, the intuitive brilliance with which he addressed San Sebastián’s topography through the unstable forms then discussed in the United States must have surprised even himself – being in general more moderate, albeit occasionally dragged into formal adventures by his restless intellectual curiosity. And in this particular project the architect claims to have successfully reconciled the pragmatic compactness of architecture with the fragmented instability of the times and the elemental materiality of minimalism.

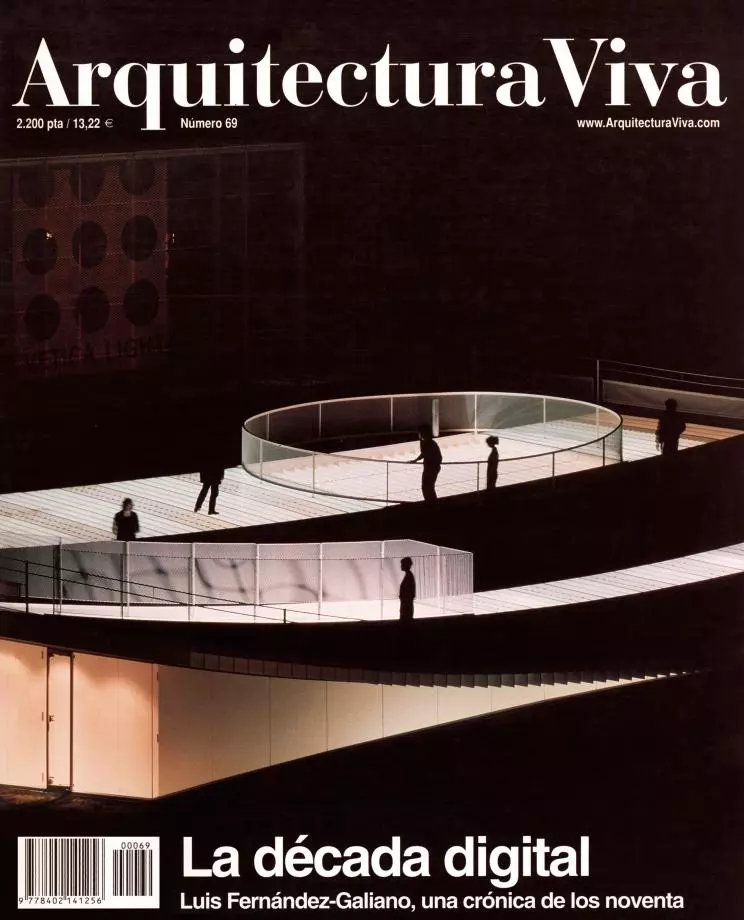

Whether a product of deliberate syncretism or random discovery, surely the Kursaal presents many different countenances: abstract from the beach, with the two cubes of grooved glass broken by a few aleatory openings, and figurative from the street, due to the succession of episodes crowned by the prisms, which, on this rear elevation, reveal the thickness of the double crystalline skin in the trough-shaped profile of the serrated roof; solid during the day, even with the watery reflections of the thick glass sheets giving the complex an evanescent materiality, and lightweight at night, when the translucent gleam of the prisms turns them into sharp slanting beacons; categorical from afar, when the geometric gesture outlines itself in the coastal landscape, and motley close up, when the variety of the materials and their encounters breaks up the building into contrasting intentions.

In the final analysis, this dazzling work shows that architecture is fuelled by ideas. The two slanted translucent cubes have so much power to summon emotions and metaphors that any other matter is subordinated to these luminous blocks, which point simultaneously to the mineral geometry of nature and the built artifice of the city; the blurred, silent light of a submarine universe and the cracking, splintered landscape of a world of ice; the ominous fractures of a terrorist ridden society and its sharp will to regenerate itself. Thus, the potency of these at once aggressive and affable prisms dissolves all anecdotal detail. The esthetic feat of the double glass skin, with the unique curving tiles that give it a dense, material tremor; the unexpected pre-fabricated pieces of slate that turn the plinth into a decorative and tactile frieze, which refers both to the architecture of Jacques Herzog and to the sculpture of Richard Long; or the clever versatility of the v-shaped beams, which hold up the terraces and collect rainwater while acting as diffusers of the artificial light within: all this pales against the evocative force of the idea. An idea which also makes unimportant the abrupt encounter of the glazing with the ground, the heterogeneous execution of slate panels, or the unnecessary profusion of materials – which culminates outside in the very Miesian marble bench of the vast lookout over the Bay of Biscay, and inside with the golden paint on the back of the auditorium tiers.

The old Kursaal was not too lucky: two years after the ribbon-cutting by Queen María Cristina, the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera illegalized gambling, halting the spinning roulettes and condemning the building to a melancholic and uncertain existence. But let us hope that the wheel of fortune will turn more benevolently for this cultural reincarnation of the old casino. Moneo’s bet, throwing his glass dice on the seaboard of this singular city, deserves a stroke of luck.