The East is at once promise and threat. As the European Union extends towards the old glacis of the Soviet Union, the rediscovery of the East brings along formidable political experiences, important economic opportunities and fertile social exchanges: the Velvet Revolutions, the enlargement of markets and the migration flows are assets that enrich both the material and the immaterial heritage of Western Europeans. Simultaneously, this bittersweet process incorporates into the Union ruling elites of a more American than European fidelity, some productive structures burdened by bureaucracy and rushed privatizations, and a few criminal mafias with less scruples than those acclimatized in the prosperous areas of the continent.

If the gaze wanders farther, to the proud Russia of Putin or to ex-Soviet republics like the Kazakhstan of Nazarbayev, where the increase in the prices of petrol and gas has fuelled an economic boom that is cast in national-religious political moulds and in authoritarian systems of social control – masked by some Kremlinologists with the use of mottoes like ‘sovereign democracy’ to describe an autocracy where the budding consumerism and a rekindled patriotism are used to justify the lack of freedom –, it is legitimate to contemplate this oriental rise with the caution of one who perceives at once the lights and the shadows of a historical period shaken by an Eastern wind that can be either beneficial breeze or devastating gale.

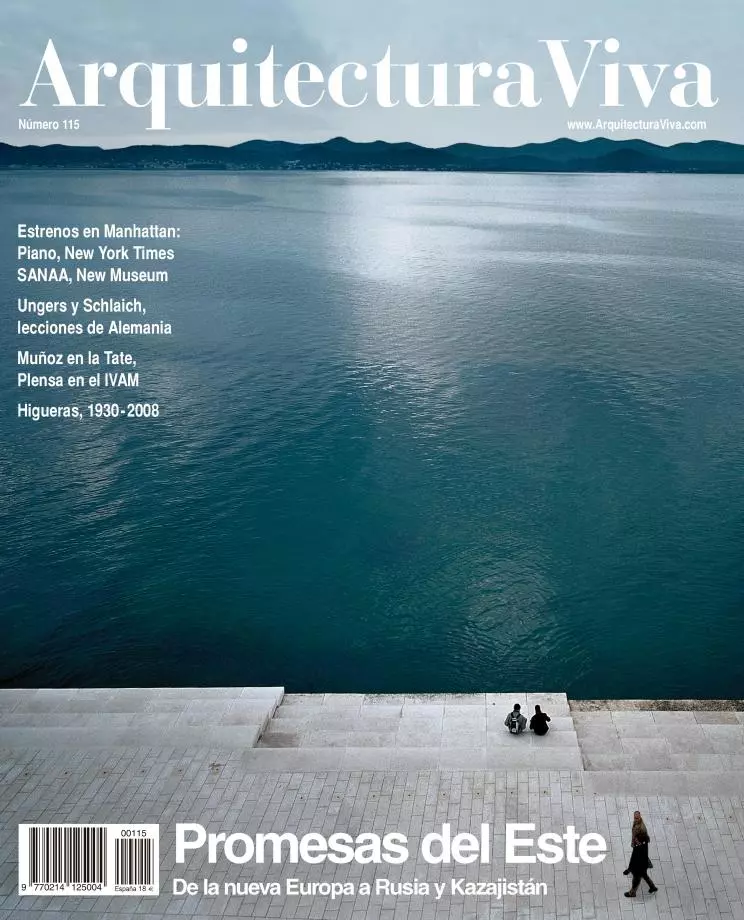

In the field of architecture, the Eastern promises have been especially fruitful in the Balkans and the Baltic, two peripheral areas that have joined today’s cosmopolitan dialogue of the forms: in a Balkan peninsula wounded by the war that fragmented Yugoslavia, both the Slovenia of Pleznik and Adriatic Croatia once again serve as hinges between the Germanic Mitteleuropa and the Mediterranean; and in the Baltic republics hesitant between the Slavic world and Scandinavia, the new buildings provide a differential identity. Not so bright is the panorama in a Hungary where the romantic vigor of Makovec has faded away or in a Czech Republic engrossed in the beauty of its heritage.

Meanwhile, both Moscow and Saint Petersburg perpetuate the secular Russian tradition of importing architects from abroad for their most representative works, and just like a Bolognese built in the 15th century the Muscovite cathedral, a Scot designed in the 17th the Kremlin domes, Frenchmen drew up in the 18th the plans of the two cities and an Italian carried out in the same century the cathedral of Saint Petersburg, today it is also international firms – mainly British ones – that refurbish the old monuments and create the new, in a construction and real-estate orgy that is echoed in the steppes of Central Asia, where a handful of foreign offices are building a new capital for a philantropic ogre.