Days of Penitence

The crisis has generated a mood of austerity in Europe and the US, but Asia or the Gulf continue to fuel a process of urban and architectural expansion.

The great Recession has generated in the West an economy of fear and a culture of repentance. Impelled or imposed by the crisis, a new austerity pervades public budgets and private concerns. Both political discourse and intellectual debate are governed by regret for the excesses and by purpose of amendment, clearing the path for a time of penitence and pentimento. In Europe, the sovereign debt cri-sis that provoked the rescues of Greece and Ireland also forced a change of direction in Spain, where a series economic reforms and social cuts poured oil on the troubled water of the markets, but did not change the unemployment rates or the increasing loss of prestige of the ruling elite. The discouragement of citizens and the paralysis of the real-estate market prompted architects to use the crisis to shed material weight and purify the spirit, going back to the basic principles of a discipline that has always set out to do more with less, supplying well-being and beauty with limited technical and economic means.

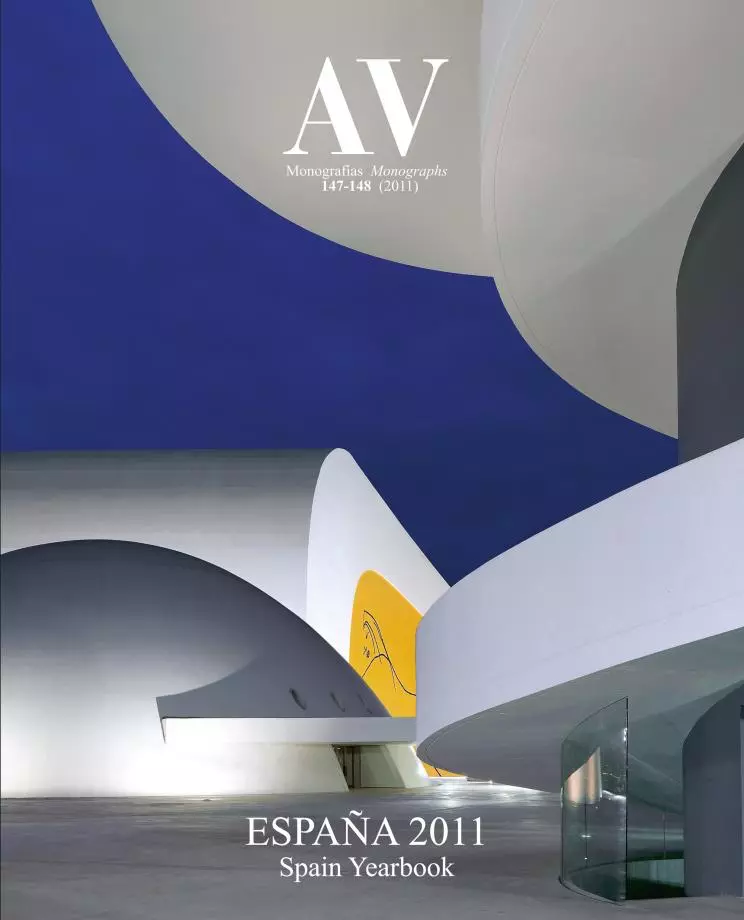

The Spanish Pavilion in Shanghai, the National Stadium of South Africa in Johannesburg and the Niemeyer Center in Avilés were a few of the iconic works completed in a year nevertheless marked by the economic recession.

But the penitential and agitated climate of Europe, with a shrinking international influ-ence, or of the United States, which sees its military and political leadership threatened by its institutional and economic disfunctions, did not spread to the rest of the world. China, which replaced Japan as second world power, celebrated its rise with the opening in Shanghai of the largest expo ever, with the shining presence of the needles of the British pavilion (Thomas Heatherwick) and the wickers of the Spanish one (Benedetta Tagliabue). Brazil, where Dilma Rousseff replaced Lula as president, advanced in the preparation of the World Cup of 2014 and the Olympic Games of 2016 in Rio, while using the 102-year-old Oscar Niemeyer to export emblematic architectures to cities like Avilés, where a new cultural center represents the will to regenerate a decaying region. South Africa, whose political transition turned Nelson Mandela into a global icon, showed its economic vigor organizing the first World Cup held in this continent, with the victory of a Spanish team that gave its country one of the few reasons for joy in the year. And the Gulf, driven by oil income, won for Qatar the bid to host the Cup in 2022, an event that will entail the construction of large stadiums that will round off the list of signature cultural works designed in the area by Foster, Nouvel, Koolhaas, Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron and other star architects.

After the rise of the West, today we are wit-nessing the so-called ‘rise of the rest’, and this historical mutation is also expressed in the dif-ferent architectural mood in the mature and the emerging economies. While Europe and the United States preach austerity and admire experiences such as those of Alejandro Aravena in Chile or Francis Kéré in Burkina Faso, carried out in contexts of scarcity, an attitude that inspired the congress held in Pamplona under the motto ‘more for less’ – first used by Buckminster Fuller, to whom an exhibition was devoted in Madrid – or the show organized by New York’s MoMA under the title “Small Scale, Big Change”, Asia and the Gulf continue to push a boundless process of urban growth and architectural development. Something similar could be said about sustainability, promoted on either side of the Atlantic with pedagogical and advertising initiatives such as Solar Decathlon – held for the first time in Washington and since 2010 every other year in Madrid, under the auspices of the United States Department of Energy and the Spanish government –, and understood in Asia as a new economic field (the manufacturing of solar panels, which China wishes to lead), or else misunderstood in the Gulf, that can simultaneously house experiments of eco-logical urbanism such as Masdar City by Foster in Abu Dhabi and appoint the same architect to build an air-conditioned stadium to host the Qatar World Cup final.

The international stage was shared by languages as varied as those of the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron at the VitraHaus, the Japanese Shigeru Ban at the Pompidou Metz or the Anglo-Iraki Zaha Hadid at the opera of Guangzhou.

This small and extraordinarily rich country of the Gulf, which by the way broke a world record with its millionaire purchase of rights over the Barcelona Football Club shirt, was also witness to the greatest international success of Spanish architecture in the year, the granting of the prestigious Aga Khan Award to the Madinat al-Zahra Museum by Fuensanta Nieto and Enrique Sobejano, who received the prize in a ceremony held in Doha. The Pritzker went to the Japanese duo Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, who picked up the award in New York’s Ellis Island and inaugurated in Europe the oneirically warped Rolex Center in Lausanne, while Sejima acted as curator of a refined and artistic Venice Architecture Bien-nale that gave Koolhaas the Golden Lion and in which young Spanish architects like Antón García-Abril, Andrés Jaque, Selgas Cano or Cero9 had a prominent presence. The section of prizes must also include Toyo Ito for the Imperiale, Ieoh Ming Pei for the RIBA Gold Medal, Peter Eisenman and David Chipperfield for the Wolf, Kéré for the Swiss Award, Manuel Gallego for the Spanish Gold, Lluís Clotet for the National Architecture Award and, last but not least, Rafael Manzano, the first Spaniard to re-ceive the conservative Driehaus, the same year in which the Pope consecrated in Barcelona the Sagrada Familia, a basilica by the already beatified Gaudí whose completion has sparked controversy over several decades.

The Spaniards Nieto & Sobejano received the Aga Khan Award for the Madinat al-Zahra Museum; for their part, Sejima & Nishizawa, who completed the Rolex Center in Lausanne, picked up the Pritzker.

Some of the most noteworthy international works completed in the year are the masterly VitraHaus by Herzog & de Meuron or the strik-ing garage by the same architects in Miami, a building by Europeans in the United States just like the museum by Piano in Los Angeles, the laboratories by Moneo at Columbia and the structures by Foster and Nouvel in the same New York, where other works were completed by Americans like Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne, Steven Holl or Diller Scofidio, who signed with Renfro and James Corner the first stretch of the remarkable High Line, a landscaping project in the heart of the city. With a divided critical reception, the Japanese Shigeru Ban presented the Pompidou of Metz, and the Anglo-Iraqi Zaha Hadid, the opera of Guangzhou; more unanimous was the reception of the projects that are transforming the social context of Co-lombian cities like Medellín and Bogotá, whose ex-mayors ran unsuccesfully as a ticket for the presidency of the country; all this in a year festively marked in Latin America by the celebration of the independence bicentennial in several countries and ominously by the earthquake of Haiti, which left hundreds of thousands of vic-tims and unimaginable devastation, worse in its consequences than the one suffered by Chile, though higher on the Richter scale and followed by a tsunami. Closer to us, several important works were partially inaugurated, such as Ei-senman’s City of Culture in Santiago, Moneo’s extension of Atocha Station or the Museum of Human Evolution by Navarro Baldeweg in Burgos; and others were completed like the Faustino Winery by Foster in Ribera del Duero, the Atrio hotel and restaurant by Mansilla & Tuñón in Cáceres, the theater by Enrique Krahe in Zafra, the dwellings by Coll & Leclerc in Pardinyes, the museum by Sancho & Madridejos in Alicante, the footbridge by RCR in Ripoll or the refurbishment of the Tàpies Foundation in Barcelona by Ábalos & Sentkiewicz.

The list of noteworthy works completed by local authors in Spain includes the Atrio hotel-restaurant by Mansilla & Tuñón in Cáceres; the footbridge by RCR in Ripoll; and the Atocha station extension by Moneo in Madrid.

Lastly, the year bode farewell to distinguished architects like Raimund Abraham, Bruce Graham and Günter Behnisch, to the theorist William Mitchell, the art collector and patron Ernst Beyeler or the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot, whose fractals had a great influence on the field of design; and in Spain, to the veterans José Antonio Corrales, Joaquín Vaquero Turcios and José Luis Picardo, and to the prematurely disappeared Bet Figueras, Carlos Asensio and Sigfrido Martín Begué. Summing up, perhaps the most significant part of the year has not so much to do with the mate-rial field of demographic movements, production flows or urban construction, but with the immaterial field of social networks. When deciding on the ‘person of the year’, the magazine Time doubted between Julian Assange or Mark Zuckerberg; the readers chose the founder of Wikileaks, whose filtered diplomatic documents triggered geopolitical earthquakes, but the edi-tors finally fell for the founder of Facebook, an example of the social networks that are trans-forming our communicative, symbolic world, but in the long run also irreversibly changing our physical environment.

Two of the international architects who opened works in Spain were Norman Foster with the Faustino Winery in Ribera del Duero and Peter Eisenman with the City of Culture of Galicia in Santiago de Compostela.